There is something magical about learning through games. Why is it so effective?

Does the brain learn more efficiently when it’s having fun? Or do the games present certain constraints and puzzles that facilitate particularly effective learning? Or is it something more mundane like games are fun and addictive and therefore we spend lots of time playing them; and it’s simply the number hours that yields impressive learning outcomes?

While there is likely some truth to all of these, I’m going to focus on the last one:

Games are fun and addictive and thus we’re willing to spend lots of time playing them.

And in the context of learning Chinese, it’s clear that quantity matters.

Escape, a case study

Our first text adventure game for learning Chinese was Escape. Our text games work like interactive graded readers. You read text descriptions about where you, what has happened, and you make choices that affect the subsequent course of the game. The games are complete with dangers and surprises, so sometimes your choices lead you to unfortunate outcomes. But no worry, you can always play again.

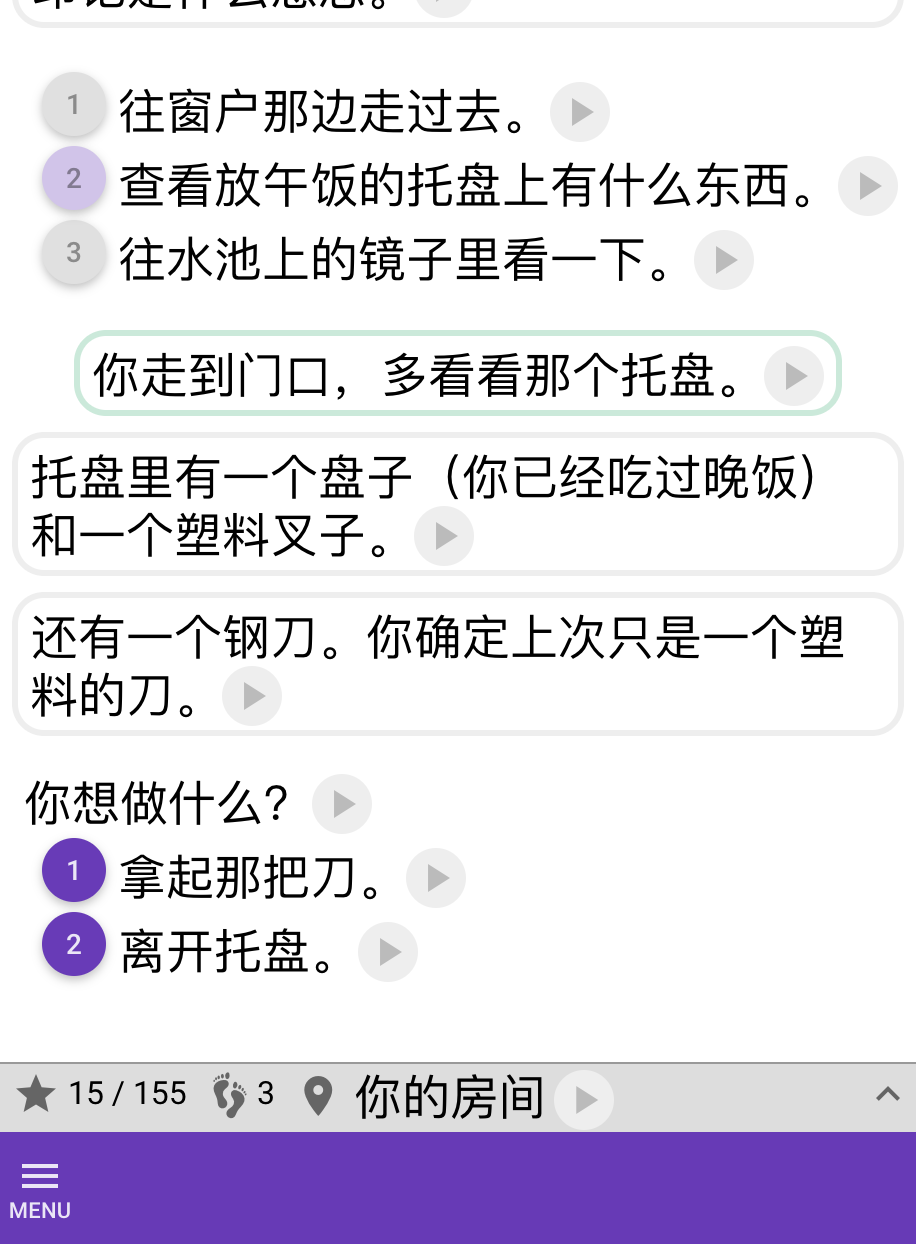

Here’s a screenshot from near the beginning of Escape:

But what concerns us here is that these games can take hours to explore and solve, resulting in a great deal of practice reading (or listening to) Chinese.

What follows is an analysis of a random sample of the games played by 100 students.1

Quantity, quantity, quantity

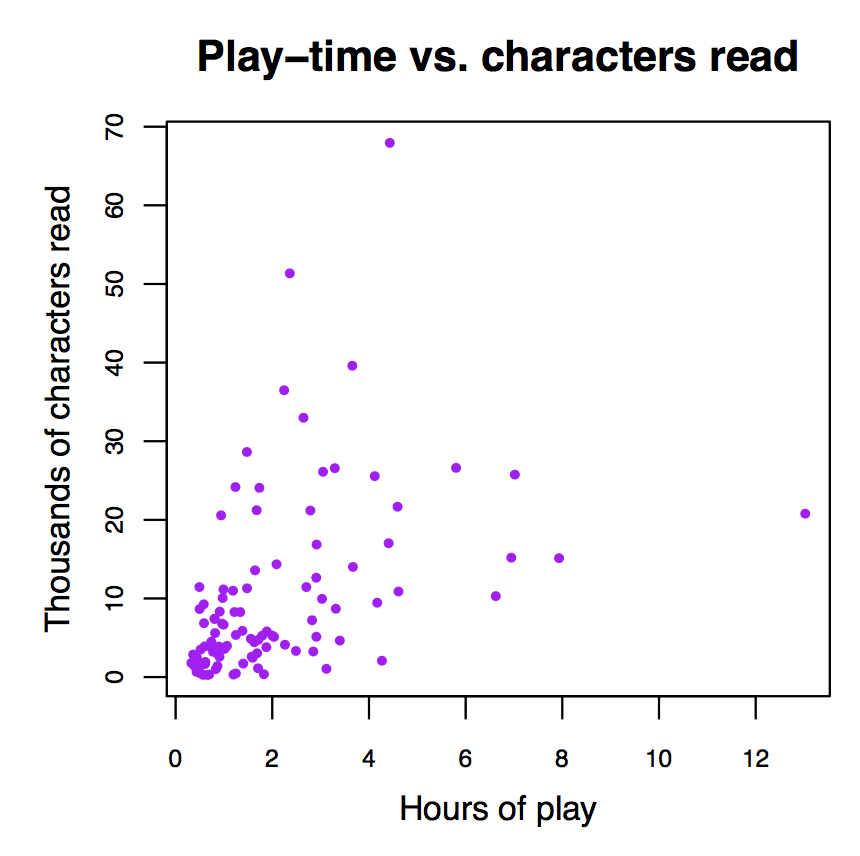

On average these students played for between 30 minutes and 13 hours (aggregating across each students’ games) and read on average 10,000 Chinese characters each and played on average 10 games each. Here’s the relationship between how many hours they played and how many characters they read:

Some students read an impressive 70,000 Chinese characters, but you can tell from this plot that there is a broad range of reading speeds, with some students reading reading more than 50k characters in just a few hours, and others taking more than 7 hours to read 10k-30k characters. This also probably reflects differences in how much time students spend re-reading text they have seen before (which is great practice, btw), how many words they look up in the dictionary, and whether they’re spending time adding words to word lists or updating their knowledge ratings.

The value of replay

For centuries, language learning methodology has employed repetition, writing Chinese characters hundreds of times, or memorizing classic texts, or more recently, using flashcards.

Repetition is helpful, but it risks being boring, causing ones mind to wander and focus to wane. This reduces its effectiveness. And what’s worse is that it’s much harder to force yourself to engage in a boring task.

But playing a game multiple times suffers much less from these problems, and still allows you many opportunities to practice familiar text. Our text adventure games are never exactly the same. Choices you make at one point in the game affect outcomes later in the game, and there are many possible paths through the game. This requires you to keep paying attention to all of the text if you want to succeed, and the desire to win is a great motivator for encouraging you to pay attention.

Chinese has thousands of characters, and given how easy they are to forget, it’s helpful to have many exposures to the characters. And while flashcard activities give you many exposures, these are not in context, making it much less useful for learning and remembering.

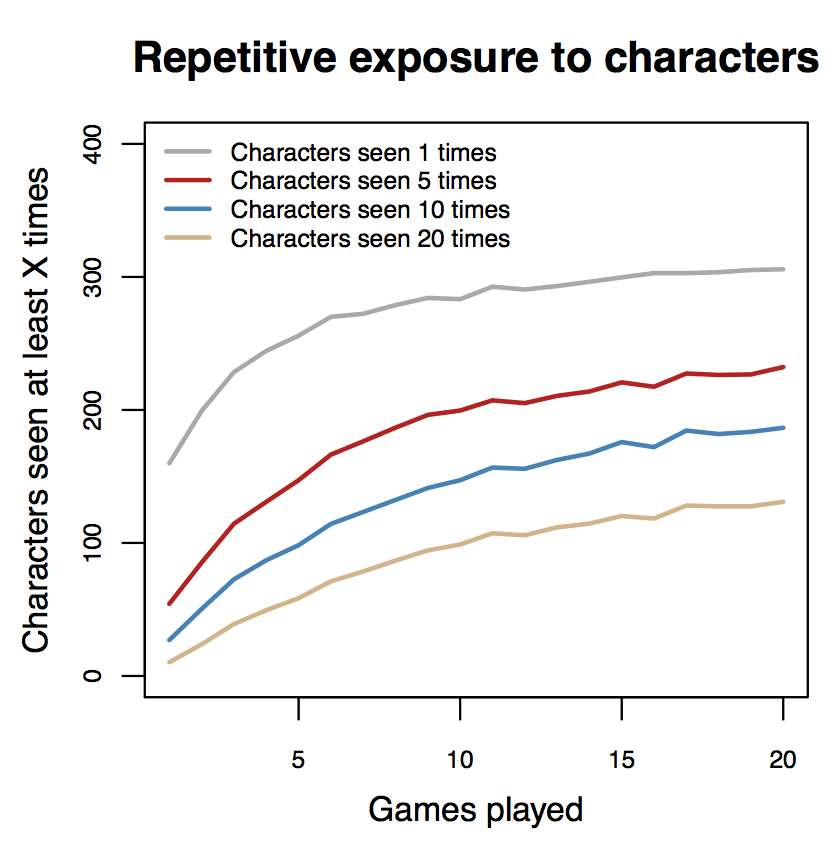

We can get a sense of how the number of times you’re exposed to the characters in the game scales with how many times you play in this next figure:

This plot shows how the number of characters you’ve seen at least once rises as a function of how many times you play the game. For example, if you’ve played five games, you probably saw about 250 characters at least once (gray line) and you probably saw 150 characters at least 5 times (red line).

In total Escape has about 400 distinct characters, so even though these students have played many games, there are still parts of the game and outcomes they have not explored.

Into the Haze

Our second game, Into the Haze, adds several game mechanics that we think make it substantially better than Escape for learning. The new mechanics include:

- Random encounters. These are scenes that can happen in different places and at different times.

- Random outcomes. Sometimes taking a certain action, like jumping across a gap in a broken highway will succeed and other times it wont.

- Resources. These are items you can gain and lose throughout the game. The most important one is your supply of air which you need to survive the poisonous haze.

The sources of randomness mean the game takes unexpected twists and turns, forcing you to pay more attention to what’s happening.

The introduction of resources, combined with random events, introduces more contingencies into the game. For example, maybe in one game a path you tried works well the first time, but when you try retracing your steps a second time, you unexpectedly lose some air, changing your calculus about which route is the best one to take.

Conclusion

Perhaps I’ve convinced you that our text adventure games are a good way expose yourself to lots of Chinese. But you don’t need to take my word for it, head over to WordSwing and try out all of our text adventure games for yourself.